June Market Pulse – central banks respond to the pandemic emergency

Chris Godding looks at who is the marginal buyer and why central banks have your back – even the long suffering European banks may be due a renaissance!

Written by Chris Godding

Published on 25 Jun 202014 minute read

Our top-down approach to investing focuses on the rate of change of three principle drivers, namely earnings momentum, monetary policy and the fiscal impulse or government spending. Given the strength of risk assets recently, I think it’s fairly clear that investors are now betting on a relatively rapid return to normal, the Powell Put and further fiscal spending.

Our top-down approach to investing focuses on the rate of change of three principle drivers, namely earnings momentum, monetary policy and the fiscal impulse or government spending. Given the strength of risk assets recently, I think it’s fairly clear that investors are now betting on a relatively rapid return to normal, the Powell Put and further fiscal spending.

The return to normal

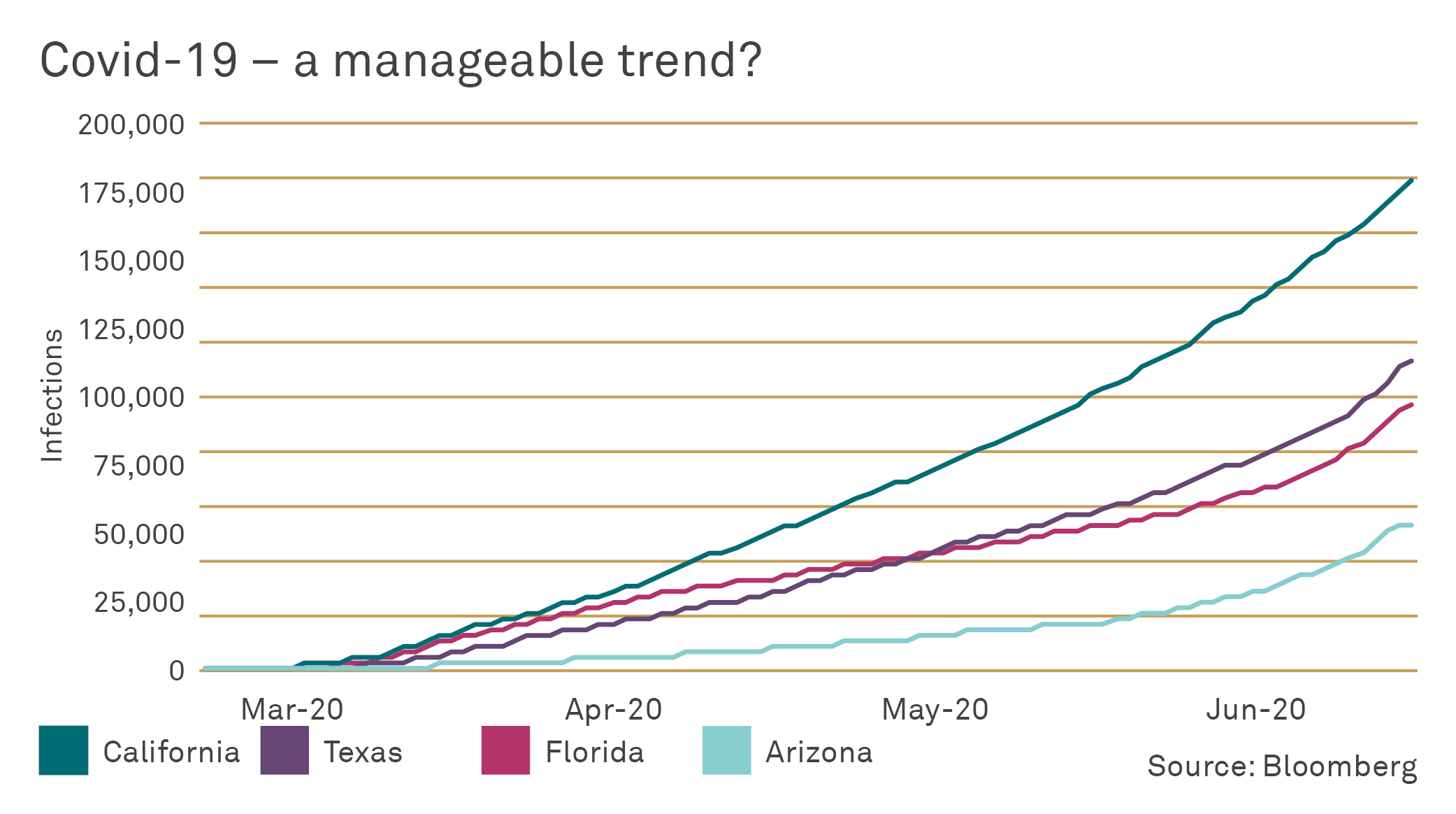

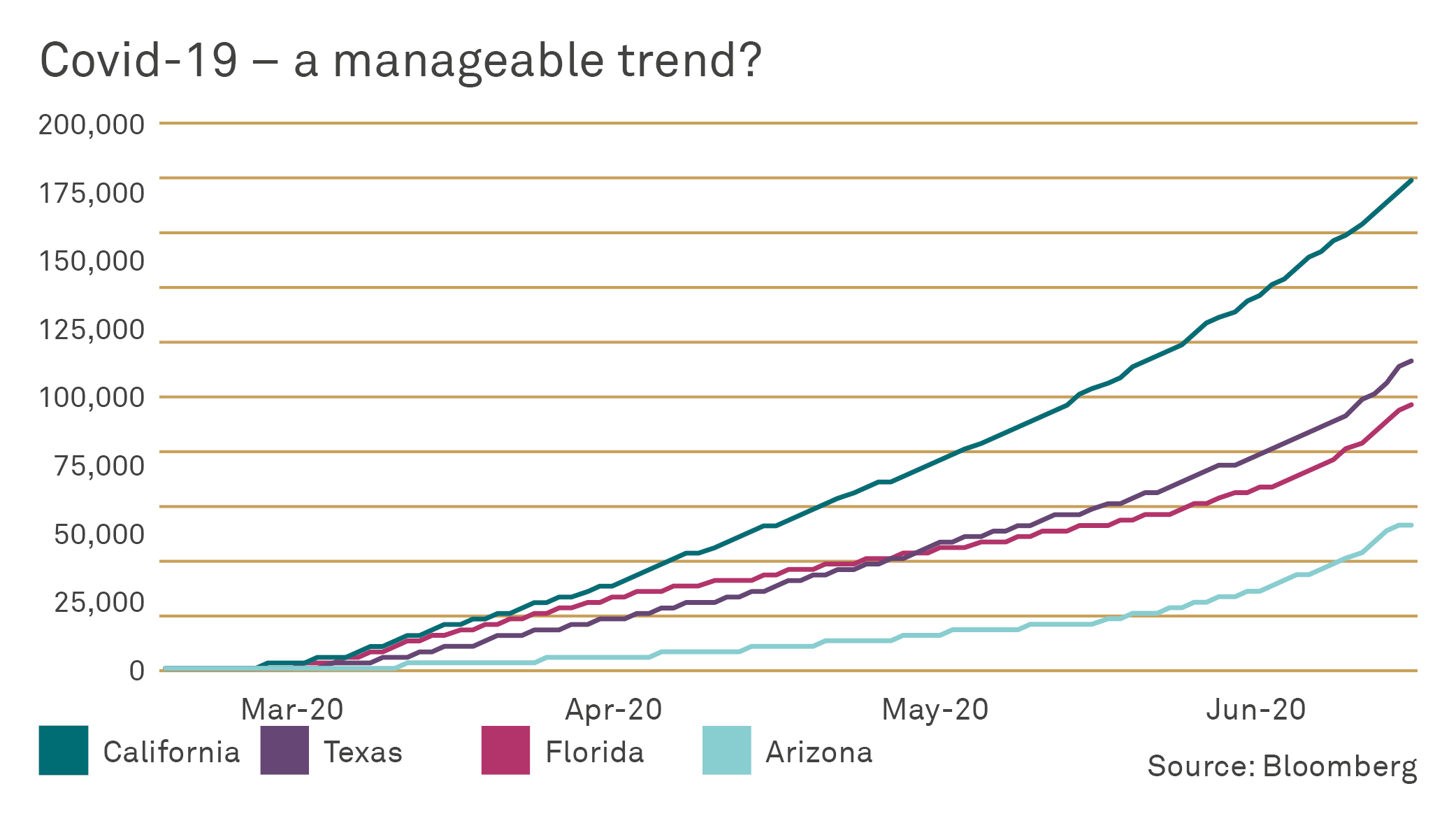

Whether the recovery of activity delivers on the hopes of the optimists largely depends on the pace of re-opening, which itself is influenced but not wholly dependent on the transmission rate (Rt) of Covid-19 around the world. Therefore, the significant flattening of infection rates where effective lockdowns have been in place has been welcome. However, there are some notable areas of concern such as India, Brazil, Sweden and some major US states where hospitalisations remain on the upward trajectory.

Texas, California, Florida and Arizona are notable both in terms of a resurgence in infections and sheer population size but, according to the latest data gathered by Deutsche Bank, almost half of US states have seen case acceleration in recent weeks. The research by Deutsche Bank suggests that a full reopening from -25% mobility back to normal would take Rt to almost exactly 1.00 nationwide – but no higher.

Sadly, very few states look like the average state. Instead, some states' transmission rates are already materially above 1 even at the same level of openness at which other states have quite low rates. There are thus large differences between states that are not explained by how open they are. These will be demographic factors such as population density (e.g. Alaska) but also the prevalence of mask-wearing or test-and-trace programmes (e.g. New York).

Taking into account the fixed demographics effects, the differences between states are so large that if each state reopened fully, more than 60% of the United States would see the virus spreading again.

The impact of higher infections and, more crucially for markets, the danger of a return to the economic pain of lockdown also depends on the need for hospitalisation and current hospital utilisation rates, which is a complex picture. In Florida and Texas for instance, hospital bed and ICU utilisation rates are currently running at 75%.

California is seeing a decline, while in Arizona the utilisation is above 85%, which must be raising some testing questions for those in authority. It is a complex situation to manage and, given that investors don’t really know the tolerance thresholds, it’s a bit like a game of chicken.

At what point does a state re-impose tighter controls and what market impact would that headline have?

If each state maximized activity subject to Rt staying below 1.00, the US economy as a whole could open more fully and more sustainably. However, this requires a degree of coordination that is not in evidence at present and is unlikely to happen. The main reason suggested by Deutsche Bank for a micro-managed approach from the Federal government is that coordination would favour greater reopening of Democratic states from here.

This is a key difference from Europe, where borders can be closed more easily to arrivals from specific countries, thus creating incentives for countries not to become 'pariahs' as currently experienced by Sweden or the UK.

Therefore, while the markets are banking on a rapid recovery, the reality may include some air-pockets and, with the MSCI World just 5% short of our target for the end of 2021, the valuation cushion is not that comforting.

There also appears to be complacency with regard to the structural damage to certain segments of the economy such as leisure, travel, entertainment and real estate, which may struggle to regain pre-Covid levels. I am an optimist on that front, believing that a vaccine will be available in early 2021, which would clearly be beneficial. However, I also recognise that it will take quite some time to inoculate the population sufficiently for the output gap and unemployment levels to decline. Ironically, investors seem to be assuming that it is better to travel, on hopeful assumptions, than to arrive, and I suspect this semi-blind optimism is likely to mean that markets defy gravity for some time. With very little in the way of real evidence to support an alternative conclusion, the equity markets are likely to focus improving confidence, low interest rates, fiscal support and money flows.

FOMO

Since the beginning of March, investors in the US took fright and increased their holding of money market funds by US$1.2 trillion to US$4.8 trillion in a panic. Hedge funds and long-only investors also reduced their exposures to the most extreme position since 2010, and now that markets have risen substantially from the lows, the result is a great deal of hand-wringing and Fear Of Missing Out.

Since the trough in March, some of this cash hoard has of course been put to work, but money market fund assets are only down a paltry US$200 billion, whilst institutional equity positioning, although off the lows, remains at the bottom of the Z-Score range.

On the hedge fund side, the CTA (momentum funds) have started to come back but remain in the 17th percentile of their average equity weighting, while the huge volatility-controlled and risk parity funds are hiding out at the 3rd and zero percentile levels. Therefore, there is a large pile of cash, currently earning zero in the bank, sitting on the side-lines to support the markets.

Current positioning data across the major asset classes tells us that equities are the least popular asset* and that positioning in the US dollar has reversed from positive to negative. The consensus long positions are in the euro and the ‘safe haven’ yen. Gold, copper and oil are all flat at the moment, which implies that the bulls and bears are not convinced either way on commodities.

The reversal in the positioning around the US dollar is particularly interesting as it informs us that the Fed has done its job effectively and the stress caused by the US dollar shortage has been solved. This is particularly good news for the minor emerging markets with a soft peg or a limited ability to sterilise US dollar fund flows to defend their currency. Assuming global economic activity improves from here and the dollar does not rally, we would expect emerging markets equities and debt to perform well. Our only worry is that China is likely to be a political punch-bag in Washington as we approach the election, so it could be quite a volatile experience for investors.

Yin and yang

The Chinese concept of yin and yang duality is where seemingly opposite forces work in a complimentary fashion and, at the moment, the emergency monetary and fiscal policies are the yin and risk assets are the yang.

The challenge for central banks in this crisis has been slightly different from the global financial crisis in that the tightening of bank regulation created a new, different lending bubble in shadow banking via the issuance of corporate debt. As official interest rates collapsed and direct bank loans dwindled due to regulations, the demand for income via corporate debt exploded. Enthusiastic investment banks, who had been on a crash diet since the collapse of mortgage backed CDOs, were eager to facilitate significant levels of debt issuance and the consequences in a crisis are predictable and not particularly pretty. Leverage remains a key concern for us in our investment strategy and hence our preference for balance sheet quality in our selection process.

Fail to prepare? Prepare to fail

Having watched the growth of shadow banking with a wary eye, the Fed and other major central banks were at least ready this time to respond to the ‘systemic threat’ and break the feedback loops quickly and effectively. Having done that, TS Lombard believe that what matters now is not the scale of the downturn, but rather how the global economy looks over the next 3-12 months, which is why Q2 data are irrelevant at this point.

While the policies announced so far have helped to support macro fundamentals through the lockdown period, in TSL’s view they will not be sufficient to prevent the global economy from settling on a weaker post-pandemic trajectory. This will inevitably have implications for the corporate credit cycle, resulting in persistent balance-sheet distress. Current financial conditions – especially in equities, but to a degree credit too – in their opinion, do not reflect this reality. Since weak balance sheets could hold back the recovery, fiscal policy must do even more to support global growth because the measures that are now in place are only sufficient to deal with a short-term growth problem.

The fact that central banks were ready for this meant that the reaction in March to the looming threat was both quick and aggressive, expanding purchases of both public and private assets. After the initial spike, purchases of government bonds are now expected to level off, but at a higher pace than that seen in previous rounds of purchases.

From the initial need to smooth out market functioning, purchases are now aimed at ensuring that the sharp rise in deficits does not cause an unwarranted tightening in financial conditions. In other words, there is a strong desire for rates to stay low across the yield curve for an extended period of time, which will naturally force investors to take on more risk if they want a positive real return.

The current policy mix is de-facto MMT (or helicopter money). Central banks buy government bonds, which then provide support to companies to keep their employees or directly pay for wages. Ultimately, central banks are writing the cheque that households are receiving and, during the lockdown, the stimulus went into excess savings. But as lockdown restrictions are eased, it is likely that there will be some pent-up demand and consumers will draw down these savings. How big this spike will be is difficult to tell at the moment, given the physiological trauma of the crisis. However, in the short term, subject to the easing of lockdown restrictions, there is a decent case for the recovery to be sharper than consensus expectations.

In the longer term, the macro strategy team at Deutsche Bank remind us that MMT or helicopter money is the textbook way of generating inflation. Inflation was always a long shot post the global financial crisis due to the massive hit to confidence and incomes, but the current policy mix is very different from the post global financial crisis period. From 2011 to 2016 central banks were using Quantitative Easing because fiscal policy was tightening while the output gap was still wide. In 2017/2018, the Fed tightened monetary policy as fiscal policy was easing. Today, central banks are easing to support the fiscal stimulus and the combination of the two could be quite powerful.

Discouraged savers

One of the most fundamental problems that developed market central banks must manage, given the uncertainty about their future employment and earnings prospects, is the tendency to increase precautionary savings. Indeed, as noted above, the personal savings rate in the US has rocketed, reaching 33% in April, not only due to the influx of stimulus checks to certain lower and middle-income households, but also reflecting an increase in the propensity to save.

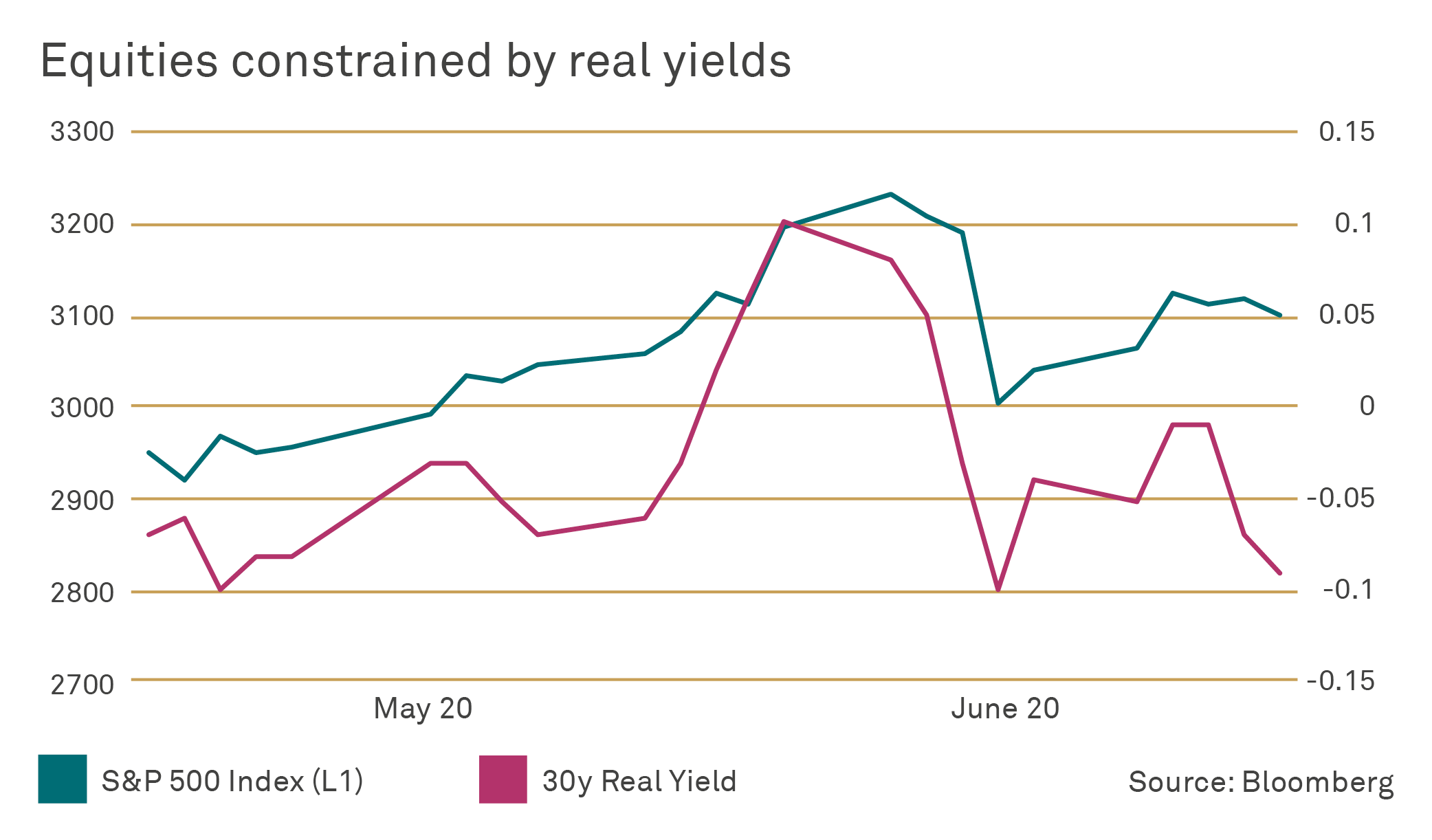

With an increase in domestic savings – and caution when it comes to corporate investment – any Keynesian would undoubtedly argue a strong case for additional fiscal stimulus. This stimulus would need to at least offset the threat of Ricardian equivalence, whereby the impact of public sector spending is to varying degrees matched by any permanent increase in private sector savings. The 5.5% of GDP difference between private net savings and public net borrowing in the US is a case in point. From this perspective, the second observation is that a clear function of Quantitative Easing is to reduce the financial incentive to save by lowering yields. To this end, it would seem reasonable to assume that the developed world’s central banks would prefer to observe deeply negative real yields and are likely to increase Quantitative Easing or alternative purchase plans in order to keep real yields low.

Again, intervention of this nature will flatten term premia and increase the incentive to invest in risky assets to enhance returns, putting upward pressure on equity prices.

The level where higher real yields begin to have a negative effect on risk assets doubtlessly fluctuates over time, but failure to contain 30-year real yields below zero currently appears to be sufficient to halt equity appreciation.

Austerity is so yesterday

In summary, negative real yields appear to be a worthwhile policy target that both minimises the Ricardian equivalence and maximises the efficacy of fiscal policy, while repairing wealth via risk asset appreciation.

Ultimately, the central banks are telling their respective governments that they will underwrite fiscal expansion by buying bonds and controlling the yield curve. They are also telling investors that you can only get a real yield by taking risk. It is an opportunity that governments should grasp with both hands and it is the last roll of the dice. After this, both the central bank and government balance sheets will be spent and so we hope the money is invested wisely and raises productivity.

If this assessment is correct, the Faustian pact between central banks and their respective governments is a policy mix that is particularly favourable to gold. Positive real yields are kryptonite for gold and it would limit the downside risk considerably if the implied policy target is negative real yields and reflation. It is the kind of asymmetry we like and gold is one of our highest conviction positions.

Europe – getting it together

My final observation this month is that Europe may finally be getting its act together when it comes to financial stability. A strong economy demands a strong financial sector, which in Europe has been a struggle in the face of tighter regulation, a failure to recognise bad debts and recapitalise and the drain of negative interest rates.

Under Mme Lagarde’s new leadership, the European Central Bank now seems ready to chew a political wasp and help out the banks for the greater good. In particular, the support provided by TLTROs (targeted longer-term refinancing operations) have become increasingly less about provision of liquidity per se and more about providing a subsidy for banks to offset the costs of negative rates and reduce the lower bound on lending rates.

If you help the banks, keep it well hidden

When the European Central Bank announced its two-tiered reserve system in September 2019, excess liquidity stood at around €1.75 trillion which, according to JP Morgan, implied a direct cost of the negative deposit rate of close to €9 billion. Around €4 billion of this cost was then shielded via tiering** based on a bank’s minimum reserves by reducing the amount of reserves subject to the negative deposit rate. However, since September, the excess liquidity has risen to €2.7 trillion, with €850 billion of this being offset via the 6x tiering multiplier and the net annual cost to banks is back up over €9 billion (€1.85 trillion at -0.5%).

In the latest evolution of this monetary gymnastics, the revised terms of the TLTROs provide a much larger ‘subsidy’ to banks compared to the €2.5 billion when tiering was announced last September. Assuming that all banks were able to meet the lending targets set out in the programme and received the -1% discounted rate on liquidity provided under the latest version of the programme (TLTRO3), the €1.63 trillion borrowed would represent a €16 billion subsidy for banks over the next 12 months, which will more than offset the direct cost of negative rates.

Needless to say, it’s complex but probably politically astute for bank subsidies to be well hidden and it is good news for a beleaguered sector, although it may be prudent for any celebrations by bank CEOs to be done while self-isolating!

Lending conditions should improve as a result of this iteration, which will support economic growth, build bank reserves and restore a positive cycle. Inflection points are not always ablaze in lights but, for someone who has been a cynical perma-pessimist on the European banking sector since 2007, this seems like an important turning point for Europe.

*Source: DB Asset Allocation & CTFC

**The two-tier system applies to average end-of-calendar-day excess reserves over the maintenance period held in reserve accounts with the euro system, but does not apply to excess liquidity held at the European Central Bank’s deposit facility. The volume of reserve holdings in excess of minimum reserve requirements that is exempt from the deposit facility rate is determined as a multiple of a credit institution’s minimum reserve requirements – what is known as the ‘allowance’. The multiplier is the same for all credit institutions. The non-exempt excess reserve holdings continue to be remunerated at zero percent or the deposit facility rate, whichever is lower. Source: European Central Bank.

Please don’t hesitate to contact us by calling 020 7189 2400 if you have any queries.

Get insights and events via email

Receive the latest updates straight to your inbox.

You may also like…

Market news

2024 Autumn Budget Overview: The key announcements from Chancellor Rachel Reeves

Market news