May Market Pulse – how will the economy change after lockdown relaxation?

Oxford Economics sees a rebound in the second half of this year, but the sudden stop means that the world GDP growth is likely to contract by 4.8% in 2020, says Chief Investment Officer Chris Godding

The value of investments can fall as well as rise and that you may not get back the amount you originally invested.

Nothing in these briefings is intended to constitute advice or a recommendation and you should not take any investment decision based on their content.

Any opinions expressed may change or have already changed.

Written by Chris Godding

Published on 26 May 202014 minute read

I remember the early days of video conferencing being incredibly frustrating, when the time delay made discussion almost impossible and the video looked like a Peter Crouch goal celebration. Fast forward and I now struggle with filling in the gaps of missing words, the stony silence of people on mute and the odd occasion when the internet connection simply decides it has had enough while I am using Zoom. I’m sure most of you are facing the same technology challenges, but you can enjoy a feeling of schadenfreude listening to Louis Theroux’s recent podcast with Helena Bonham Carter. Even the BBC is learning how to function in the New World Order, but let’s just hope we avoid the dystopian future depicted in the eponymous video by Ministry!

Fortunately, we are now seeing a return to normality in many parts of the world as lockdown measures are relaxed. Mobility data provided by Deutsche Bank show that driving in the US is now almost back to January levels on a seven-day average basis, with a few of the individual data points in recent days actually exceeding the baseline rate. Mobility data for Germany, Canada and Russia trail slightly, but all continue to see greater movement in recent weeks, even ahead of some restrictions being officially lifted. Brazil, Russia and India, however, are still seeing large case growth, probably due to a gradual approach to lockdown. Globally, the confirmed cases are likely to be just under 6 million as we enter June and the confirmed deaths may be as high as 375,000. That said, the macro team at Deutsche looking at the Covid-19 statistics make the fascinating observation that since 1 February and across all age group in the USA, more people have died from pneumonia than Covid-19.

There is also good news from the Oxford Vaccine Group who is beginning trials of a vaccine candidate and Moderna in the USA has developed a vaccine that shows early signs that it can create an immune-system response to the coronavirus. This was from a Phase One study led by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and Moderna said it expects Phase Three trial initiation in July. Realistically, this implies that a vaccine could be available in early 2021.

Needless to say, the economic impact of the virus has been mounting, with multiple examples of record-breaking negative data, particularly in employment, retail spending and activity in the services sector. Oxford Economics still sees a rebound in the second half of this year, but the sudden stop means that world GDP growth is likely to contract by 4.8% in 2020. Their current forecast is that global GDP will return to its Q4 2019 level by early 2021, but they do not expect the level of GDP to converge to the forecast path seen prior to the Covid-19 outbreak due to shifts in behaviour such as increased precautionary savings. They also caveat their forecast by saying the risks are “large and heavily skewed to the downside”. Their prognosis for the UK is a little gloomier, with hard data for March suggesting that the impact of the lockdown on activity has been severe. The 2020 UK GDP forecast is now a fall of 7.9% and they do not expect GDP to return to its end-2019 level until Q4 2021. However, this degree of contraction is not out of line with the averages of the developed world.

China is currently the best guide to recovery as it is further along the path to normality but, even here, weak domestic and external demand present a challenge to the outlook. GDP growth in China is now forecast at just 0.8% in 2020 compared to the 6% growth expected at the beginning of the year.

Summary of the current economic forecasts from Oxford Economics

|

|

Real GDP (% Year) |

Inflation (% Year) |

||||

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

|

USA |

2.3 |

-7.0 |

8.6 |

1.8 |

0.1 |

1.2 |

|

Eurozone |

1.2 |

-7.6 |

6.2 |

1.2 |

0.2 |

1.5 |

|

UK |

1.4 |

-7.9 |

7.3 |

1.8 |

0.8 |

1.4 |

|

Japan |

0.7 |

-6.0 |

3.7 |

0.5 |

-0.4 |

0.1 |

|

China |

6.1 |

0.8 |

8.5 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

1.6 |

|

World |

2.5 |

-4.8 |

7.0 |

3.2 |

2.6 |

2.5 |

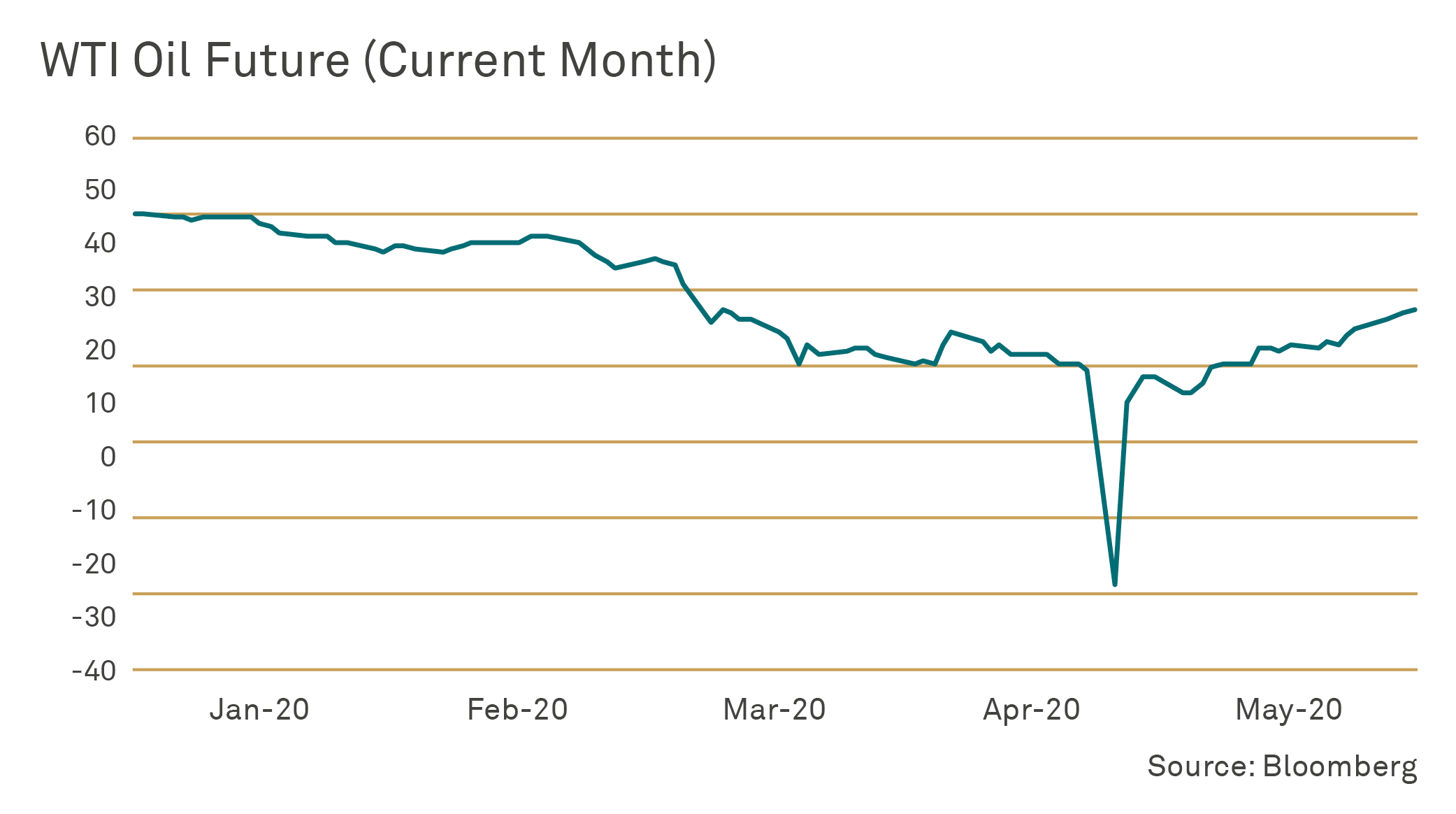

Expectations of a recovery and a vaccine are now fuelling a very strong rebound in financial assets, buoyed by the massive fiscal and monetary injections discussed in last month’s edition. Oil is literally the fuel of activity and a particularly sensitive high-frequency barometer over recent weeks, going from a spot price of -US$40, when reserves were piling up with nowhere to go, to US$34 as I type. Supply reductions from OPEC and an additional unilateral cut from Saudi Arabia have helped, but the real boost has been a recovery in demand.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) now sees global oil demand at 99.9 million barrels a day in 2020, down around 90,000 barrels a day from 2019, a sharp downgrade from their forecast in February, which predicted global oil demand would grow by 825,000 barrels a day this year.

The short-term outlook for the oil market will ultimately depend on how effective policies are in containing the coronavirus outbreak and any lingering impact on economic activity.

To account for this extreme uncertainty facing energy markets, the IEA has developed two other scenarios for how global oil demand could evolve this year that starkly illustrate the range of possible outcomes. In a more pessimistic low case, global measures fail to contain the virus and global demand falls by 730,000 barrels a day in 2020. In a more optimistic high case, the virus is contained quickly around the world, and global demand grows by 480,000 barrels a day. In other words, they have no idea.

Typically, lower oil prices are a positive for global activity, but in the current highly uncertain environment, the impact may be more equivocal for a number of reasons. An average oil price of US$30 would deliver a negative inflation impulse for a worrying chunk of the global economy. While this normally would lead to modestly higher real income growth, such income gains may not boost spending much today, given the pessimism regarding coronavirus and the subdued consumer and business confidence. US$30 oil also raises the prospect of downgrades and defaults by energy producers who will have to slash investment and the resulting negative trickledown effect. Despite these factors, Oxford Economics still believes the overall influence of a lower oil price will be a net positive of approximately 0.3% on global GDP in 2020 and 2021, and that the peak impact on global inflation would be felt in 2020, when it eases by 1.1pp below the baseline.

Absolute price aside and, most importantly, the recent recovery in the oil price clearly tells us that the real economy, and not just financial markets, is apparently past the trough.

Equity markets and other risk assets took their cue about a month earlier, reacting as we suggested they would to the coordinated stimulus measures and well ahead of normalisation in the real world. The MSCI All Country World index is currently up 28%, driven by a stellar performance from the US and the largest cap companies in particular. Despite a truly momentous collapse in earnings expectations across the board, investors have leapt to the conclusion that we will see a sharp recovery in 2021 and that the huge liquidity injections by global central banks would support and inflate financial assets.

While it is definitely possible that this scenario plays out, it is definitely not the only possibility and, in the case of the US, investors do appear to be putting an awful lot of eggs in one basket.

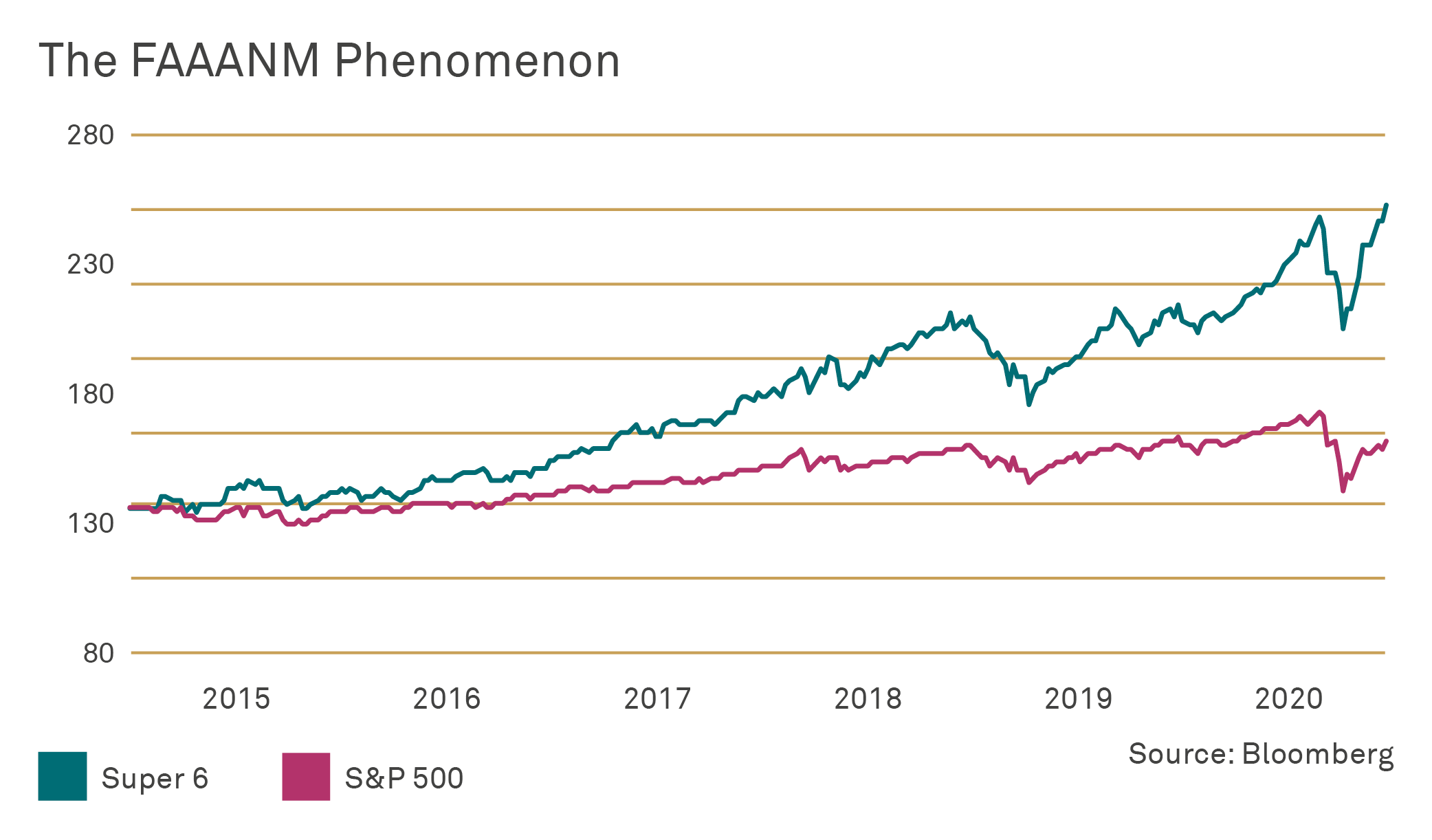

Gerard Minack of Minack Advisors points out this month that “the exceptional performance of the US equity market doesn’t rely on the US economy, or on Fed policy, or on fiscal stimulus. It relies on a handful of companies: Facebook, Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Netflix & Microsoft (FAAANM). Exclude those six global franchise stories and the US market looks much like everyone else’s – earnings flat-lining with sales under pressure – except that it trades at significant valuation premium [to other world markets]”. Minack goes on to say that the historic superiority of the S&P 500 versus other major world indices is solely down to the superiority of those six companies and “in line with the desultory earnings performance of global equities excluding the US”. The shocking reality is that there has been no major change in forecast earnings for the remaining S&P 494 since 2015.

The result of their superiority is the spectacular market performance of the FAAANM cohort. The market capitalisation of the S&P500 has increased by US$6 trillion since the start of 2015, of which the Super 6 contributed US$4 trillion. The Super 6 have also accounted for all the increase in forecast profits over the same period.

As a collective they are a market in themselves. The market capitalisation of the Super 6 is now larger than any non-US equity market aside from China. However, this S&P 6 trade at an average P/E of 45x next year’s earnings versus 18x for the S&P500 and 14x for the MSCI World Ex-US.

Minack avoids the trap of calling the top on these stocks, acknowledging the superiority of their revenue and earnings growth to date, but they obviously represent a massive concentration risk that is very sensitive to the discount rate and the assumption that the lack of investment and productivity of the majority of the past few years will continue for the foreseeable future. Whether that argument holds up if spending shifts from the damaged consumer to government and investment over the next ten years is, in my view, debatable.

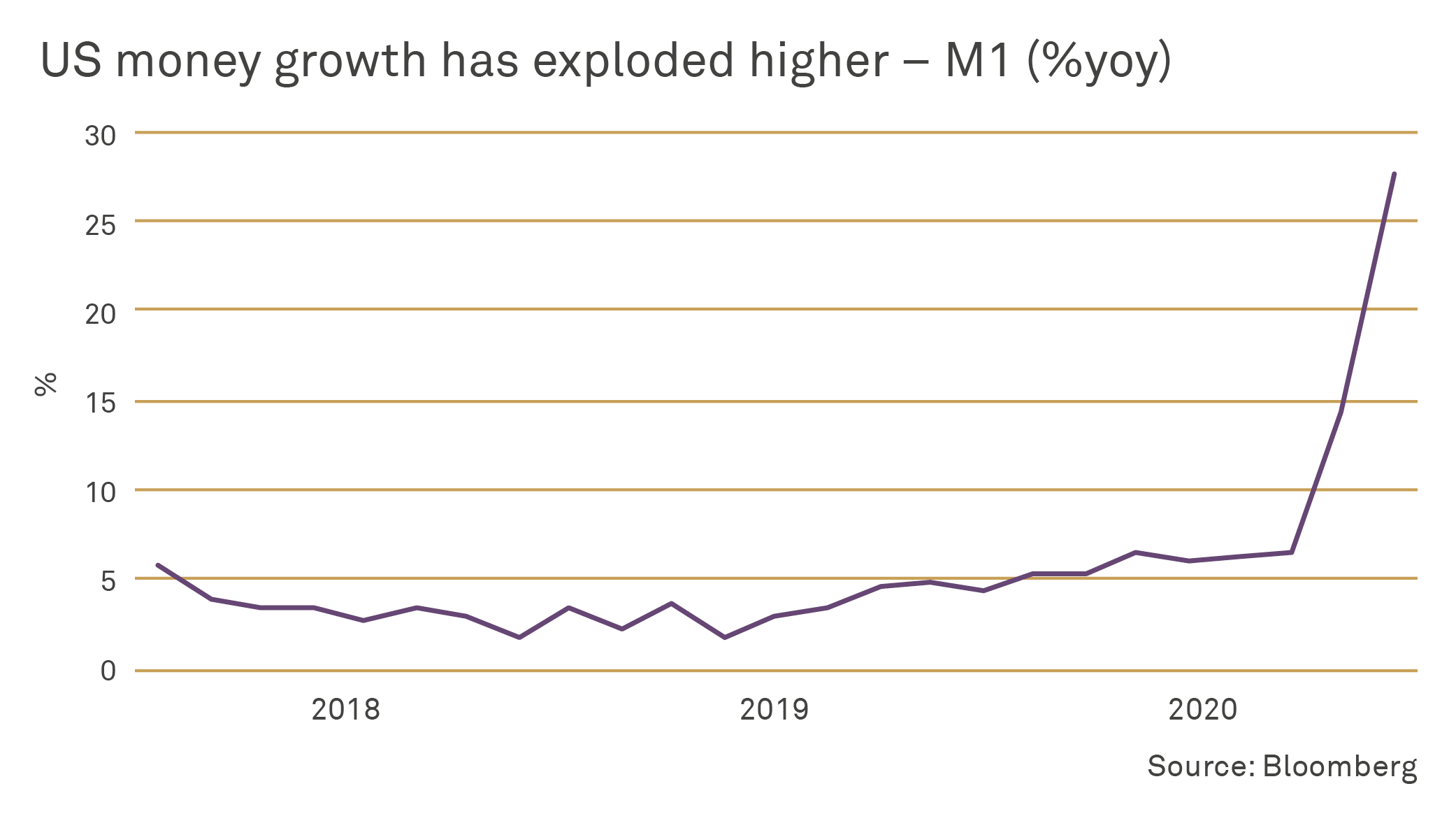

For the moment, the ever-decreasing and supportive discount rate for the Super 6 does not appear to be changing. However, longer term, the large monetization of debt and the pushing of bond yields to around 0% (while necessary) will reduce the appeal of holding dollar and other reserve-currency-denominated debt on the principal that it is highly inflationary. Exploding government balance sheets at the same time have also moved the ‘liquidity impulse’ to a new level.

In the UK, Andrew Bailey at the Bank of England is even contemplating a move to negative interest rates – don’t do it Andrew please, it doesn’t work! – and France and Germany are talking of “grants” to the countries most affected by Covid-10 – things must be bad!

The prospect for inflation as a consequence of all this stimulus is one of the questions we are grappling with and it is too early to reach a conclusion. In the short term, if demand picks up quickly, there may well be a supply shortage and demand-led inflation as a result.

Given the circumstances, it would be politically convenient for inflation to rise. What better way to reduce the value of debt as a percentage of GDP than to inflate it away. On the other hand, the experience of previous crises suggests that deflation will simply lead to misery.

We also believe governments will resist the urge to tighten the fiscal belt and deflate demand prematurely this time. The political zeitgeist had already turned firmly against austerity before this current crisis hit and the post-WW2 model of reflation seems a guide to what works best in such situations.

However, it will be a hard fought battle to reflate developed economies after such a structural shock and the deflationary camp points to the output gap created by a massive recession, combined with the fact that it will take households years to rebuild their balance sheets.

Central banks are certainly supportive of a drive for higher inflation and Chief North America Economist at PIMCO, Tiffany Wilding, recently wrote that “the Fed will likely, for a time, tolerate or even target inflation above its 2% longer-term objective. And according to [PIMCO] inflation forecasts, this will likely leave interest rates at the zero lower bound well into 2022. By linking guidance to inflationary outcomes, and perhaps even announcing a formal yield curve target two to three years out, the Fed can help ensure the economy benefits from continued easy monetary conditions.”

PIMCO forecast that the Fed’s balance sheet will reach a peak level of around US$8.5 trillion, versus a US$4.2 trillion pre-pandemic level, with the risks tilted towards more. In addition to asset purchases to stimulate the economy, they also point out that the Fed has announced various other lending and liquidity facilities, with US$2.5 trillion in total lending capacity, designed to backstop markets and which could grow larger if market conditions again deteriorate.

Over the next several quarters, monetary conditions are therefore likely to remain very supportive. However, PIMCO believe the Fed will want to strengthen its forward guidance on interest rates to help ensure that markets price in a path that is in line with their own expectations, which suggests to me that the Fed is throwing down the gauntlet to anyone who threatens a riot in the bond market.

Inflation has proven to be a difficult objective since the financial crisis, but with G7 annual broad money growth at its highest since 1970, the rumoured death of globalisation and an end to austerity, we might actually make it this time. Simon Ward of Janus Henderson argues that the failure in the past has been due to a faster fall in the velocity of the circulation of money, which has been in trend decline for 50+ years. He argues that excess money simply created wealth in real and financial assets and, subsequently, a faster fall in velocity as a result of an economic shock – like the current one – would imply a stronger path for asset prices and wealth over the medium term. However, my observation would be that if there is an implicit supply shock to the economy that destroys excess capital, then the returns on capital are restored to the point where investment and velocity rise. This should be good news for the stagnant earnings of the MSCI World Ex the Super 6 who make it through the crisis. Returns on capital are likely to exceed the cost of capital for quite some time and any additional fiscal spending, as opposed to the austerity of the past, would also lead to an improvement in velocity.

Post the GFC, my work on the velocity of money clearly indicated a deflationary headwind that I now believe is beginning to veer. Not that I believe inflation is going to burst onto the stage overnight, but in our portfolios we have added to gold and are adding a new position in long-dated inflation linked bonds as insurance. Our preference is to buy protection when it is cheap and not when we have to.

For those of you looking for light relief, next month’s piece is likely to be returning to the Brexit debate and the 30 June deadline for an extension to the withdrawal agreement. The political appeal from Boris Johnson’s perspective would be to dodge blame for the disaster of a no-deal Brexit by compounding it with the economic disaster of Covid-19, provided he  'kitchen-sinks' the bad news before the end of this year. A fear that is weighing on the performance of UK equities and the pound despite their apparent compelling value.

'kitchen-sinks' the bad news before the end of this year. A fear that is weighing on the performance of UK equities and the pound despite their apparent compelling value.

Please don’t hesitate to contact us by calling 020 7189 2400 if you have any queries.

Get insights and events via email

Receive the latest updates straight to your inbox.

You may also like…

Market news

2024 Autumn Budget Overview: The key announcements from Chancellor Rachel Reeves

Market news